What Were the Distinctive Beliefs Philosophies and Arts of Greek Civilization

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy connected throughout the Hellenistic period and the menses in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ideals, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric and aesthetics.[1]

Greek philosophy has influenced much of Western culture since its inception. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: "The safest general label of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a serial of footnotes to Plato".[2] Articulate, unbroken lines of influence lead from ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophers to Roman philosophy, Early on Islamic philosophy, Medieval Scholasticism, the European Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment.[3]

Greek philosophy was influenced to some extent by the older wisdom literature and mythological cosmogonies of the aboriginal Virtually East, though the extent of this influence is widely debated. The classicist Martin Litchfield W states, "contact with oriental cosmology and theology helped to liberate the early Greek philosophers' imagination; it certainly gave them many suggestive ideas. But they taught themselves to reason. Philosophy as we empathise it is a Greek creation".[four]

Subsequent philosophic tradition was then influenced by Socrates every bit presented by Plato that it is conventional to refer to philosophy developed prior to Socrates every bit pre-Socratic philosophy. The periods following this, up to and later the wars of Alexander the Swell, are those of "Classical Greek" and "Hellenistic philosophy", respectively.

Pre-Socratic philosophy [edit]

The convention of terming those philosophers who were agile prior to the death of Socrates as the pre-Socratics gained currency with the 1903 publication of Hermann Diels' Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, although the term did not originate with him.[five] The term is considered useful considering what came to be known as the "Athenian school" (equanimous of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle) signaled the rising of a new approach to philosophy; Friedrich Nietzsche'southward thesis that this shift began with Plato rather than with Socrates (hence his nomenclature of "pre-Ideal philosophy") has non prevented the predominance of the "pre-Socratic" distinction.[vi]

The pre-Socratics were primarily concerned with cosmology, ontology, and mathematics. They were distinguished from "not-philosophers" insofar equally they rejected mythological explanations in favor of reasoned discourse.[7]

Milesian school [edit]

Thales of Miletus, regarded by Aristotle as the first philosopher,[eight] held that all things arise from a single fabric substance, water.[9] Information technology is non because he gave a cosmogony that John Burnet calls him the "first man of science," just because he gave a naturalistic explanation of the cosmos and supported it with reasons.[10] According to tradition, Thales was able to predict an eclipse and taught the Egyptians how to mensurate the elevation of the pyramids.[eleven]

Thales inspired the Milesian school of philosophy and was followed past Anaximander, who argued that the substratum or arche could not be water or any of the classical elements but was instead something "unlimited" or "indefinite" (in Greek, the apeiron). He began from the observation that the world seems to consist of opposites (e.g., hot and cold), even so a thing tin become its opposite (e.thousand., a hot thing cold). Therefore, they cannot truly exist opposites but rather must both be manifestations of some underlying unity that is neither. This underlying unity (substratum, arche) could not be any of the classical elements, since they were one farthermost or another. For example, water is wet, the opposite of dry, while fire is dry, the opposite of moisture.[12] This initial state is ageless and imperishable, and everything returns to it according to necessity.[13] Anaximenes in turn held that the arche was air, although John Burnet argues that by this, he meant that information technology was a transparent mist, the aether.[14] Despite their varied answers, the Milesian school was searching for a natural substance that would remain unchanged despite appearing in different forms, and thus represents 1 of the first scientific attempts to answer the question that would pb to the development of mod atomic theory; "the Milesians," says Burnet, "asked for the φύσις of all things."[15]

Xenophanes [edit]

Xenophanes was born in Ionia, where the Milesian schoolhouse was at its most powerful and may have picked up some of the Milesians' cosmological theories as a upshot.[16] What is known is that he argued that each of the phenomena had a natural rather than divine explanation in a manner reminiscent of Anaximander's theories and that there was only ane god, the world as a whole, and that he ridiculed the anthropomorphism of the Greek religion by claiming that cattle would claim that the gods looked like cattle, horses like horses, and lions like lions, merely as the Ethiopians claimed that the gods were snub-nosed and black and the Thracians claimed they were pale and red-haired.[17]

Xenophanes was highly influential to subsequent schools of philosophy. He was seen as the founder of a line of philosophy that culminated in Pyrrhonism,[18] mayhap an influence on Eleatic philosophy, and a precursor to Epicurus' full break betwixt science and religion.[19]

Pythagoreanism [edit]

Pythagoras lived at roughly the same fourth dimension that Xenophanes did and, in dissimilarity to the latter, the school that he founded sought to reconcile religious conventionalities and reason. Little is known about his life with whatever reliability, however, and no writings of his survive, and so it is possible that he was simply a mystic whose successors introduced rationalism into Pythagoreanism, that he was but a rationalist whose successors are responsible for the mysticism in Pythagoreanism, or that he was really the writer of the doctrine; there is no way to know for certain.[20]

Pythagoras is said to take been a disciple of Anaximander and to have imbibed the cosmological concerns of the Ionians, including the idea that the cosmos is synthetic of spheres, the importance of the space, and that air or aether is the arche of everything.[21] Pythagoreanism also incorporated ascetic ethics, emphasizing purgation, metempsychosis, and consequently a respect for all animal life; much was made of the correspondence between mathematics and the cosmos in a musical harmony.[22] Pythagoras believed that behind the appearance of things, in that location was the permanent principle of mathematics, and that the forms were based on a transcendental mathematical relation.[23]

Heraclitus [edit]

Heraclitus must take lived afterward Xenophanes and Pythagoras, as he condemns them along with Homer as proving that much learning cannot teach a man to recollect; since Parmenides refers to him in the past tense, this would identify him in the 5th century BCE.[24] Contrary to the Milesian school, which posits one stable element as the arche, Heraclitus taught that panta rhei ("everything flows"), the closest element to this eternal flux being fire. All things come to laissez passer in accordance with Logos,[25] which must exist considered equally "plan" or "formula",[26] and "the Logos is mutual".[27] He also posited a unity of opposites, expressed through dialectic, which structured this flux, such as that seeming opposites in fact are manifestations of a common substrate to adept and evil itself.[28]

Heraclitus called the oppositional processes ἔρις (eris), "strife", and hypothesized that the apparently stable land of δίκη (dikê), or "justice", is the harmonic unity of these opposites.[29]

Eleatic philosophy [edit]

Parmenides of Elea cast his philosophy confronting those who held "information technology is and is not the same, and all things travel in reverse directions,"—presumably referring to Heraclitus and those who followed him.[thirty] Whereas the doctrines of the Milesian school, in suggesting that the substratum could appear in a diversity of different guises, implied that everything that exists is corpuscular, Parmenides argued that the first principle of being was One, indivisible, and unchanging.[31] Beingness, he argued, by definition implies eternality, while just that which is can be thought; a thing which is, moreover, cannot be more or less, and then the rarefaction and condensation of the Milesians is incommunicable regarding Existence; lastly, every bit movement requires that something exist autonomously from the thing moving (viz. the space into which it moves), the One or Beingness cannot motility, since this would crave that "space" both exist and not exist.[32] While this doctrine is at odds with ordinary sensory experience, where things practise indeed change and move, the Eleatic school followed Parmenides in denying that sense phenomena revealed the world equally it really was; instead, the only affair with Being was thought, or the question of whether something exists or non is ane of whether it can be thought.[33]

In support of this, Parmenides' pupil Zeno of Elea attempted to evidence that the concept of motility was cool and every bit such motion did not exist. He also attacked the subsequent development of pluralism, arguing that information technology was incompatible with Existence.[34] His arguments are known as Zeno'due south paradoxes.

Pluralism and atomism [edit]

The power of Parmenides' logic was such that some subsequent philosophers abandoned the monism of the Milesians, Xenophanes, Heraclitus, and Parmenides, where one matter was the arche, and adopted pluralism, such as Empedocles and Anaxagoras.[35] There were, they said, multiple elements which were not reducible to one another and these were set in motion past love and strife (every bit in Empedocles) or past Mind (as in Anaxagoras). Agreeing with Parmenides that there is no coming into being or passing away, genesis or decay, they said that things appear to come into being and laissez passer abroad considering the elements out of which they are composed assemble or disassemble while themselves being unchanging.[36]

Leucippus too proposed an ontological pluralism with a cosmogony based on two main elements: the vacuum and atoms. These, by means of their inherent movement, are crossing the void and creating the existent material bodies. His theories were not well known past the time of Plato, nonetheless, and they were ultimately incorporated into the work of his student, Democritus.[37]

Sophism [edit]

Sophism arose from the juxtaposition of physis (nature) and nomos (law). John Burnet posits its origin in the scientific progress of the previous centuries which suggested that Being was radically different from what was experienced by the senses and, if comprehensible at all, was not comprehensible in terms of gild; the world in which people lived, on the other manus, was one of police and order, admitting of humankind's own making.[38] At the same time, nature was constant, while what was by police force differed from one place to another and could be changed.

The first person to call themselves a sophist, according to Plato, was Protagoras, whom he presents equally teaching that all virtue is conventional. It was Protagoras who claimed that "man is the mensurate of all things, of the things that are, that they are, and of the things that are non, that they are not," which Plato interprets equally a radical perspectivism, where some things seem to be one way for one person (and so actually are that way) and another mode for another person (so actually are that way also); the determination being that one cannot look to nature for guidance regarding how to live 1'south life.[39]

Protagoras and subsequent sophists tended to teach rhetoric as their primary vocation. Prodicus, Gorgias, Hippias, and Thrasymachus announced in diverse dialogues, sometimes explicitly teaching that while nature provides no upstanding guidance, the guidance that the laws provide is worthless, or that nature favors those who act against the laws.

Classical Greek philosophy [edit]

Socrates [edit]

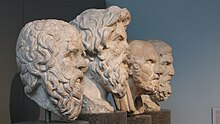

Four Greek philosophers: Socrates, Antisthenes, Chrysippos, Epicurus; British Museum

Socrates, believed to have been born in Athens in the 5th century BC, marks a watershed in ancient Greek philosophy. Athens was a center of learning, with sophists and philosophers traveling from across Greece to teach rhetoric, astronomy, cosmology, and geometry.

While philosophy was an established pursuit prior to Socrates, Cicero credits him as "the showtime who brought philosophy down from the heavens, placed it in cities, introduced it into families, and obliged it to examine into life and morals, and good and evil."[twoscore] By this account he would exist considered the founder of political philosophy.[41] The reasons for this turn toward political and upstanding subjects remain the object of much study.[42] [43]

The fact that many conversations involving Socrates (equally recounted by Plato and Xenophon) end without having reached a house determination, or aporetically,[44] has stimulated debate over the meaning of the Socratic method.[45] Socrates is said to take pursued this probing question-and-respond way of examination on a number of topics, usually attempting to go far at a defensible and attractive definition of a virtue.

While Socrates' recorded conversations rarely provide a definite answer to the question under examination, several maxims or paradoxes for which he has get known recur. Socrates taught that no one desires what is bad, and and then if anyone does something that truly is bad, information technology must be unwillingly or out of ignorance; consequently, all virtue is knowledge.[46] [47] He often remarks on his own ignorance (claiming that he does non know what courage is, for instance). Plato presents him as distinguishing himself from the common run of mankind by the fact that, while they know nothing noble and good, they exercise non know that they do non know, whereas Socrates knows and acknowledges that he knows zero noble and proficient.[48]

The groovy statesman Pericles was closely associated with this new learning and a friend of Anaxagoras, yet, and his political opponents struck at him by taking advantage of a bourgeois reaction against the philosophers; information technology became a crime to investigate the things in a higher place the heavens or below the world, subjects considered impious. Anaxagoras is said to have been charged and to have fled into exile when Socrates was about twenty years of age.[49] There is a story that Protagoras, too, was forced to flee and that the Athenians burned his books.[50] Socrates, withal, is the only subject recorded as charged under this law, convicted, and sentenced to death in 399 BCE (see Trial of Socrates). In the version of his defence force voice communication presented by Plato, he claims that it is the envy he arouses on business relationship of his being a philosopher that will convict him.

Numerous subsequent philosophical movements were inspired by Socrates or his younger associates. Plato casts Socrates as the principal interlocutor in his dialogues, deriving from them the basis of Platonism (and by extension, Neoplatonism). Plato's student Aristotle in turn criticized and congenital upon the doctrines he ascribed to Socrates and Plato, forming the foundation of Aristotelianism. Antisthenes founded the school that would come to be known as Cynicism and accused Plato of distorting Socrates' teachings. Zeno of Citium in plough adapted the ideals of Cynicism to articulate Stoicism. Epicurus studied with Platonic and Pyrrhonist teachers before renouncing all previous philosophers (including Democritus, on whose atomism the Epicurean philosophy relies). The philosophic movements that were to dominate the intellectual life of the Roman Empire were thus born in this febrile period post-obit Socrates' activeness, and either direct or indirectly influenced past him. They were also absorbed by the expanding Muslim world in the 7th through tenth centuries Advertizement, from which they returned to the W as foundations of Medieval philosophy and the Renaissance, equally discussed below.

Plato [edit]

Plato was an Athenian of the generation afterwards Socrates. Aboriginal tradition ascribes thirty-six dialogues and thirteen letters to him, although of these only twenty-iv of the dialogues are at present universally recognized as authentic; about modern scholars believe that at to the lowest degree twenty-eight dialogues and two of the letters were in fact written by Plato, although all of the thirty-half-dozen dialogues have some defenders.[51] A further nine dialogues are ascribed to Plato but were considered spurious even in antiquity.[52]

Plato's dialogues characteristic Socrates, although non always as the leader of the conversation. (One dialogue, the Laws, instead contains an "Athenian Stranger.") Along with Xenophon, Plato is the main source of information about Socrates' life and beliefs and information technology is not always easy to distinguish between the two. While the Socrates presented in the dialogues is frequently taken to exist Plato'southward mouthpiece, Socrates' reputation for irony, his caginess regarding his own opinions in the dialogues, and his occasional absenteeism from or modest role in the chat serve to muffle Plato'south doctrines.[53] Much of what is said nigh his doctrines is derived from what Aristotle reports about them.

The political doctrine ascribed to Plato is derived from the Democracy, the Laws, and the Statesman. The showtime of these contains the proffer that in that location will not be justice in cities unless they are ruled by philosopher kings; those responsible for enforcing the laws are compelled to hold their women, children, and property in mutual; and the individual is taught to pursue the common practiced through noble lies; the Democracy says that such a city is likely impossible, however, mostly bold that philosophers would refuse to rule and the people would refuse to compel them to do then.[54]

Whereas the Republic is premised on a distinction between the sort of knowledge possessed past the philosopher and that possessed by the king or political human, Socrates explores only the character of the philosopher; in the Statesman, on the other hand, a participant referred to as the Eleatic Stranger discusses the sort of cognition possessed past the political human being, while Socrates listens quietly.[54] Although rule by a wise human being would be preferable to dominion by law, the wise cannot assistance just be judged by the unwise, and so in practice, rule by police is deemed necessary.

Both the Republic and the Statesman reveal the limitations of politics, raising the question of what political order would be best given those constraints; that question is addressed in the Laws, a dialogue that does non take place in Athens and from which Socrates is absent.[54] The graphic symbol of the society described there is eminently conservative, a corrected or liberalized timocracy on the Spartan or Cretan model or that of pre-autonomous Athens.[54]

Plato'southward dialogues too have metaphysical themes, the about famous of which is his theory of forms. It holds that not-fabric abstract (but substantial) forms (or ideas), and not the material world of alter known to us through our physical senses, possess the highest and well-nigh fundamental kind of reality.

Plato oftentimes uses long-form analogies (usually allegories) to explicate his ideas; the most famous is perhaps the Allegory of the Cavern. It likens most humans to people tied upwards in a cavern, who look just at shadows on the walls and have no other conception of reality.[55] If they turned around, they would see what is casting the shadows (and thereby proceeds a further dimension to their reality). If some left the cave, they would meet the outside globe illuminated by the dominicus (representing the ultimate form of goodness and truth). If these travelers then re-entered the cavern, the people within (who are notwithstanding only familiar with the shadows) would not be equipped to believe reports of this 'outside world'.[56] This story explains the theory of forms with their unlike levels of reality, and advances the view that philosopher-kings are wisest while most humans are ignorant.[57] One student of Plato (who would become another of the most influential philosophers of all time) stressed the implication that agreement relies upon first-mitt ascertainment.

Aristotle [edit]

Aristotle moved to Athens from his native Stageira in 367 BC and began to study philosophy (perhaps fifty-fifty rhetoric, under Isocrates), eventually enrolling at Plato'south University.[58] He left Athens approximately twenty years later to report phytology and zoology, became a tutor of Alexander the Swell, and ultimately returned to Athens a decade subsequently to establish his own school: the Lyceum.[59] At least twenty-nine of his treatises have survived, known as the corpus Aristotelicum, and address a variety of subjects including logic, physics, optics, metaphysics, ideals, rhetoric, politics, poetry, botany, and zoology.

Aristotle is often portrayed every bit disagreeing with his instructor Plato (e.thou., in Raphael's School of Athens). He criticizes the regimes described in Plato'south Republic and Laws,[60] and refers to the theory of forms as "empty words and poetic metaphors."[61] He is generally presented equally giving greater weight to empirical ascertainment and practical concerns.

Aristotle's fame was non bang-up during the Hellenistic period, when Stoic logic was in vogue, merely later on peripatetic commentators popularized his piece of work, which eventually contributed heavily to Islamic, Jewish, and medieval Christian philosophy.[62] His influence was such that Avicenna referred to him just as "the Primary"; Maimonides, Alfarabi, Averroes, and Aquinas every bit "the Philosopher."

Aristotle opposed the utopian style of theorizing, deciding to rely on the understood and observed behaviors of people in reality to formulate his theories. Stemming from an underlying moral assumption that life is valuable, the philosopher makes a point that scarce resources ought to be responsibly allocated to reduce poverty and death. This 'fear of goods' led Aristotle to exclusively support 'natural' trades in which personal satiation was kept at natural limit of consumption.[63] 'Unnatural' trade, every bit opposed to the intended limit, was classified every bit the acquisition of wealth to attain more wealth instead of to purchase more appurtenances.[64] [63] Cut more along the grain of reality, Aristotle did non only set his mind on how to requite people direction to make the right choices but wanted each person equipped with the tools to perform this moral duty. In his own words, "Property should be in a certain sense common, just, as a general dominion, private; for, when everyone has a distinct interest, men will not mutter of one some other, and they will brand more than progress considering everyone volition be attention to his own business... And further, there is the greatest pleasure in doing a kindness or service to friends or guests or companions, which tin can only be rendered when a man has private property. These advantages are lost past excessive unification of the land." [sixty]

Pessimism [edit]

Cynicism was founded by Antisthenes, who was a disciple of Socrates, as well equally Diogenes, his contemporary.[65] Their aim was to live according to nature and against convention.[65] Antisthenes was inspired by the ascetism of Socrates, and accused Plato of pride and conceit.[66] Diogenes, his follower, took the ideas to their limit, living in extreme poverty and engaging in anti-social behaviour. Crates of Thebes was, in plow, inspired by Diogenes to give away his fortune and live on the streets of Athens.[67]

Cyrenaicism [edit]

The Cyrenaics were founded past Aristippus of Cyrene, who was a educatee of Socrates. The Cyrenaics were hedonists and held that pleasance was the supreme good in life, especially physical pleasure, which they thought more intense and more desirable than mental pleasures.[68] Pleasure is the only practiced in life and pain is the only evil. Socrates had held that virtue was the only human being skilful, merely he had as well accepted a limited role for its commonsensical side, allowing pleasure to be a secondary goal of moral action.[69] Aristippus and his followers seized upon this, and made pleasure the sole last goal of life, denying that virtue had whatever intrinsic value.

Megarians [edit]

The Megarian school flourished in the fourth century BC. Information technology was founded by Euclides of Megara, one of the pupils of Socrates. Its ethical teachings were derived from Socrates, recognizing a single good, which was apparently combined with the Eleatic doctrine of Unity. Their work on modal logic, logical conditionals, and propositional logic played an important role in the development of logic in artifact, and were influences on the subsequent creation of Stoicism and Pyrrhonism.

Hellenistic philosophy [edit]

The philosopher Pyrrho of Elis, in an anecdote taken from Sextus Empiricus' Outlines of Pyrrhonism

PLISTARCHI • FILIVS

translation (from Latin): Pyrrho • Greek • Son of Plistarchus

HANC ILLIVS IMITARI

SECVRITATEM translation (from Latin): It is correct wisdom then that all imitate this security (Pyrrho pointing at a peaceful squealer munching his food)

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, many dissimilar schools of thought adult in the Hellenistic world and then the Greco-Roman globe. In that location were Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Syrians and Arabs who contributed to the development of Hellenistic philosophy. Elements of Persian philosophy and Indian philosophy also had an influence. The spread of Christianity throughout the Roman earth, followed past the spread of Islam, ushered in the finish of Hellenistic philosophy and the beginnings of Medieval philosophy, which was dominated by the three Abrahamic traditions: Jewish philosophy, Christian philosophy, and early Islamic philosophy.

Pyrrhonism [edit]

Pyrrho of Elis, a Democritean philosopher, traveled to India with Alexander the Great's ground forces where Pyrrho was influenced by Buddhist teachings, about particularly the three marks of existence.[70] Subsequently returning to Greece, Pyrrho started a new schoolhouse of philosophy, Pyrrhonism, which taught that information technology is 1'southward opinions about non-evident matters (i.e., dogma) that prevent ane from attaining eudaimonia. Pyrrhonism places the attainment of ataraxia (a state of self-possession) every bit the way to accomplish eudaimonia. To bring the mind to ataraxia Pyrrhonism uses epoché (interruption of judgment) regarding all non-axiomatic propositions. Pyrrhonists dispute that the dogmatists – which includes all of Pyrrhonism'south rival philosophies – have institute truth regarding non-evident matters. For whatever non-axiomatic matter, a Pyrrhonist makes arguments for and against such that the matter cannot be ended, thus suspending belief and thereby inducing ataraxia.

Epicureanism [edit]

Epicurus studied in Athens with Nausiphanes, who was a follower of Democritus and a student of Pyrrho of Elis.[71] He accepted Democritus' theory of atomism, with improvements made in response to criticisms by Aristotle and others.[72] His ideals were based on "the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain".[73] This was, however, not uncomplicated hedonism, every bit he noted that "We do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or of sensuality . . . we mean the absence of pain in the trunk and trouble in the mind".[73]

Stoicism [edit]

The founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium, was taught by Crates of Thebes, and he took up the Carper ideals of continence and self-mastery, but practical the concept of apatheia (indifference) to personal circumstances rather than social norms, and switched shameless flouting of the latter for a resolute fulfillment of social duties.[74] Logic and physics were besides part of early Stoicism, further developed by Zeno'southward successors Cleanthes and Chrysippus.[75] Their metaphysics was based in materialism, which was structured by logos, reason (just also chosen God or fate).[76] Their logical contributions still feature in gimmicky propositional calculus.[77] Their ideals was based on pursuing happiness, which they believed was a product of 'living in accord with nature'.[78] This meant accepting those things which i could not modify.[78] One could therefore choose whether to exist happy or not by adjusting ane's attitude towards their circumstances, as the freedom from fears and desires was happiness itself.[79]

Platonism [edit]

Academic skepticism [edit]

Effectually 266 BC, Arcesilaus became head of the Platonic Academy, and adopted skepticism as a central tenet of Platonism, making Platonism nearly the aforementioned as Pyrrhonism.[fourscore] After Arcesilaus, Academic skepticism diverged from Pyrrhonism.[81] This skeptical period of ancient Platonism, from Arcesilaus to Philo of Larissa, became known as the New Academy, although some ancient authors added further subdivisions, such every bit a Middle Academy. The Academic skeptics did non doubtfulness the being of truth; they merely doubted that humans had the capacities for obtaining it.[82] They based this position on Plato's Phaedo, sections 64–67,[83] in which Socrates discusses how noesis is non accessible to mortals.[84] While the objective of the Pyrrhonists was the attainment of ataraxia, subsequently Arcesilaus the Academic skeptics did not concord up ataraxia as the cardinal objective. The Academic skeptics focused on criticizing the dogmas of other schools of philosophy, in particular of the dogmatism of the Stoics. They acknowledged some vestiges of a moral police inside, at best but a plausible guide, the possession of which, however, formed the real stardom between the sage and the fool.[82] Slight equally the divergence may appear between the positions of the Academic skeptics and the Pyrrhonists, a comparison of their lives leads to the conclusion that a practical philosophical moderation was the characteristic of the Academic skeptics[82] whereas the objectives of the Pyrrhonists were more psychological.

Middle Platonism [edit]

Post-obit the end of the skeptical menses of the Academy with Antiochus of Ascalon, Platonic idea entered the flow of Middle Platonism, which absorbed ideas from the Peripatetic and Stoic schools. More farthermost syncretism was done by Numenius of Apamea, who combined information technology with Neopythagoreanism.[85]

Neoplatonism [edit]

Also affected past the neopythagoreans, the neoplatonists, commencement of them Plotinus, argued that listen exists before matter, and that the universe has a singular crusade which must therefore be a unmarried mind.[86] As such, neoplatonism became essentially a religion, and had not bad touch on Gnosticism and Christian theology.[86]

Transmission of Greek philosophy in the Medieval Catamenia [edit]

During the Middle Ages, Greek ideas were largely forgotten in Western Europe due to the decline in literacy during the Migration Period. In the Byzantine Empire, however, Greek ideas were preserved and studied. Islamic philosophers such equally Al-Kindi (Alkindus), Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) too reinterpreted these works after the caliphs authorized the gathering of Greek manuscripts and hired translators to increment their prestige. During the High Middle Ages Greek philosophy re-entered the West through both translations from Arabic to Latin and original Greek manuscripts from the Byzantine Empire.[87] The re-introduction of these philosophies, accompanied past the new Arabic commentaries, had a great influence on Medieval philosophers such every bit Thomas Aquinas.

Run into also [edit]

- Aboriginal philosophy

- Byzantine philosophy

- Definitions of philosophy

- Dehellenization

- English language words of Greek origin

- International scientific vocabulary

- Listing of ancient Greek philosophers

- Translingualism

- Transliteration of Greek into English

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Ancient Greek philosophy, Herodotus, famous aboriginal Greek philosophers. Ancient Greek philosophy at Hellenism.Net". world wide web.hellenism.internet . Retrieved 2019-01-28 .

- ^ Alfred North Whitehead (1929), Process and Reality, Part Ii, Chap. I, Sect. I.

- ^ Kevin Scharp (Department of Philosophy, Ohio State University) – Diagrams Archived 2014-10-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Griffin, Jasper; Boardman, John; Murray, Oswyn (2001). The Oxford history of Greece and the Hellenistic globe. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Printing. p. 140. ISBN978-0-19-280137-1.

- ^ Greg Whitlock, preface to The Pre-Platonic Philosophers, by Friedrich Nietzsche (Urbana: Academy of Illinois Printing, 2001), xiv–sixteen.

- ^ Greg Whitlock, preface to The Pre-Ideal Philosophers, past Friedrich Nietzsche (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001), xiii–nineteen.

- ^ John Burnet, Greek Philosophy: Thales to Plato, tertiary ed. (London: A & C Black Ltd., 1920), iii–16. Scanned version from Internet Annal

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics Alpha, 983b18.

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics Alpha, 983 b6 eight–xi.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 3–4, eighteen.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 18–20; Herodotus, Histories, I.74.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 22–24.

- ^ Guthrie, W. K. C.; Guthrie, William Keith Chambers (May 14, 1978). A History of Greek Philosophy: Book 1, The Before Presocratics and the Pythagoreans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521294201 – via Google Books.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 21.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 27.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 35.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 35; Diels-Kranz, Dice Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, Xenophanes frs. xv–16.

- ^ Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica Chapter XVII

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 33, 36.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 37–38.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 38–39.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 40–49.

- ^ C.Thou. Bowra 1957 The Greek experience p. 166"

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 57.

- ^ DK B1.

- ^ pp. 419ff., W.K.C. Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy, vol. 1, Cambridge University Printing, 1962.

- ^ DK B2.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 57–63.

- ^ DK B80

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 64.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 66–67.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 68.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 67.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 82.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 69.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 70.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 94.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 105–10.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 113–17.

- ^ Marcus Tullius Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, Five 10–eleven (or V IV).

- ^ Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History (Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 1953), 120.

- ^ Seth Benardete, The Statement of the Action (Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, 2000), 277–96.

- ^ Laurence Lampert, How Philosophy Became Socratic (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

- ^ Cf. Plato, Republic 336c & 337a, Theaetetus 150c, Apology of Socrates 23a; Xenophon, Memorabilia 4.4.9; Aristotle, Sophistical Refutations 183b7.

- ^ West.Grand.C. Guthrie, The Greek Philosophers (London: Methuen, 1950), 73–75.

- ^ Terence Irwin, The Development of Ethics, vol. i (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2007), 14

- ^ Gerasimos Santas, "The Socratic Paradoxes", Philosophical Review 73 (1964): 147–64, 147.

- ^ Amends of Socrates 21d.

- ^ Debra Nails, The People of Plato (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002), 24.

- ^ Nails, People of Plato, 256.

- ^ John Chiliad. Cooper, ed., Complete Works, by Plato (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997), v–6, viii–xii, 1634–35.

- ^ Cooper, ed., Complete Works, by Plato, five–six, viii–xii.

- ^ Leo Strauss, The Metropolis and Man (Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 1964), 50–51.

- ^ a b c d Leo Strauss, "Plato", in History of Political Philosophy, ed. Leo Strauss and Joseph Cropsey, third ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1987): 33–89.

- ^ "Plato – Allegory of the cave" (PDF). classicalastrologer.files.wordpress.com.

- ^ "Allegory of the Cave". washington.edu.

- ^ Kemerling, Garth. "Plato: The Republic 5–10". philosophypages.com.

- ^ Carnes Lord, Introduction to The Politics, by Aristotle (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984): 1–29.

- ^ Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1972).

- ^ a b Aristotle, Politics, bk. 2, ch. i–half dozen.

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics, 991a20–22.

- ^ Robin Smith, "Aristotle'due south Logic," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2007).

- ^ a b Kishtainy, Niall. A little history of economics : revised version. ISBN978-0-300-20636-iv. OCLC 979259190.

- ^ Reynard, H.; Gray, Alexander (December 1931). "The Development of Economic Doctrine". The Economic Journal. 41 (164): 636. doi:ten.2307/2224006. ISSN 0013-0133. JSTOR 2224006.

- ^ a b Grayling 2019, p. 99.

- ^ Grayling 2019, p. 100.

- ^ Grayling 2019, p. 102.

- ^ Annas, Julia (1995). The Morality of Happiness. Oxford University Printing. p. 231. ISBN0-19-509652-5.

- ^ Reale, Giovanni; Catan, John R. (1986). A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Origins to Socrates. SUNY Printing. p. 271. ISBN0-88706-290-iii.

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Come across with Early on Buddhism in Fundamental Asia (PDF). Princeton Academy Printing. p. 28. ISBN9781400866328.

- ^ Grayling 2019, p. 103.

- ^ Grayling 2019, p. 104.

- ^ a b Grayling 2019, p. 106.

- ^ Grayling 2019, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Grayling 2019, p. 108.

- ^ Grayling 2019, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Grayling 2019, p. 110.

- ^ a b Grayling 2019, p. 112.

- ^ Grayling 2019, p. 114.

- ^ Sextus Empiricus, "Outlines of Pyrrhonism" I.33.232

- ^ Sextus Empiricus, "Outlines of Pyrrhonism" I.33.225–231

- ^ a b c

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Arcesilaus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Arcesilaus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. - ^ "Plato, Phaedo, page 64". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Veres, Máté (2009). "Carlos Lévy, Les Scepticismes; Markus Gabriel, Antike und moderne Skepsis zur Einführung". Rhizai. A Journal for Ancient Philosophy and Science. 6 (one): 107. : 111

- ^ Eduard Zeller, Outlines of the History of Greek Philosophy, 13th Edition, page 309

- ^ a b Grayling 2019, p. 124.

- ^ Lindberg, David. (1992) The Ancestry of Western Scientific discipline. Academy of Chicago Press. p. 162.

References [edit]

- Baird, Forrest Due east.; Kaufmann, Walter (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN978-0-xiii-158591-ane.

- Nikolaos Bakalis (2005). Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Assay and Fragments, Trafford Publishing ISBN 1-4120-4843-5

- John Burnet, Early Greek Philosophy(Archived from the original, half-dozen February 2015), 1930.

- Freeman, Charles (1996). Egypt, Greece and Rome . Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-19-815003-9.

- Grayling, A. C. (2019-11-05). The History of Philosophy. Penguin. ISBN978-1-9848-7875-five.

- William Keith Chambers Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 1, The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 1962.

- Søren Kierkegaard, On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, 1841.

- A.A. Long. Hellenistic Philosophy. University of California, 1992. (2nd Ed.)

- Martin Litchfield Due west, Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1971.

- Martin Litchfield Due west, The Due east Face of Helicon: Due west Asiatic Elements in Greek Poesy and Myth, Oxford [England] ; New York: Clarendon Printing, 1997.

Further reading [edit]

- Clark, Stephen. 2012. Ancient Mediterranean Philosophy: An Introduction. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Curd, Patricia, and D.Westward. Graham, eds. 2008. The Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Gaca, Kathy L. 2003. The Making of Fornication: Eros, Ideals, and Political Reform in Greek Philosophy and Early on Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Printing.

- Garani, Myrto and David Konstan eds. 2014. The Philosophizing Muse: The Influence of Greek Philosophy on Roman Poetry. Pierides, 3. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Gill, Mary Louise, and Pierre Pellegrin. 2009. A Companion to Ancient Greek Philosophy. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hankinson, R.J. 1999. Crusade and Explanation in Ancient Greek Thought. Oxford: Oxford Academy Printing.

- Hughes, Bettany. 2010. The Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens and the Search for the Good Life. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Kahn, C.H. 1994. Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett

- Luchte, James. 2011. Early Greek Idea: Before the Dawn. New York: Continuum.

- Martín-Velasco, María José and María José García Blanco eds. 2016. Greek Philosophy and Mystery Cults. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Nightingale, Andrea W. 2004. Glasses of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy: Theoria in its Cultural Context. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- O'Grady, Patricia. 2002. Thales of Miletus. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Preus, Anthony. 2010. The A to Z of Ancient Greek Philosophy. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow.

- Reid, Heather 50. 2011. Athletics and Philosophy in the Aboriginal Globe: Contests of Virtue. Ethics and Sport. London; New York: Routledge.

- Wolfsdorf, David. 2013. Pleasure in Ancient Greek Philosophy. Key Themes in Ancient Philosophy. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Aboriginal Greek philosophy at Wikimedia Eatables

Media related to Aboriginal Greek philosophy at Wikimedia Eatables - Ancient Greek Philosophy, entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Ancient Greek Philosophers, Worldhistorycharts.com

- The Touch on of Greek Culture on Normative Judaism from the Hellenistic Period through the Heart Ages c. 330 BCE – 1250 CE

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Ancient Greek Philosophy and important Greek philosophers, Hellenism.Net

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_philosophy

0 Response to "What Were the Distinctive Beliefs Philosophies and Arts of Greek Civilization"

Post a Comment